Review: Why I Didn't Go To Your Funeral by Colin Pope

- Whitney Kerutis

- Jul 17, 2019

- 4 min read

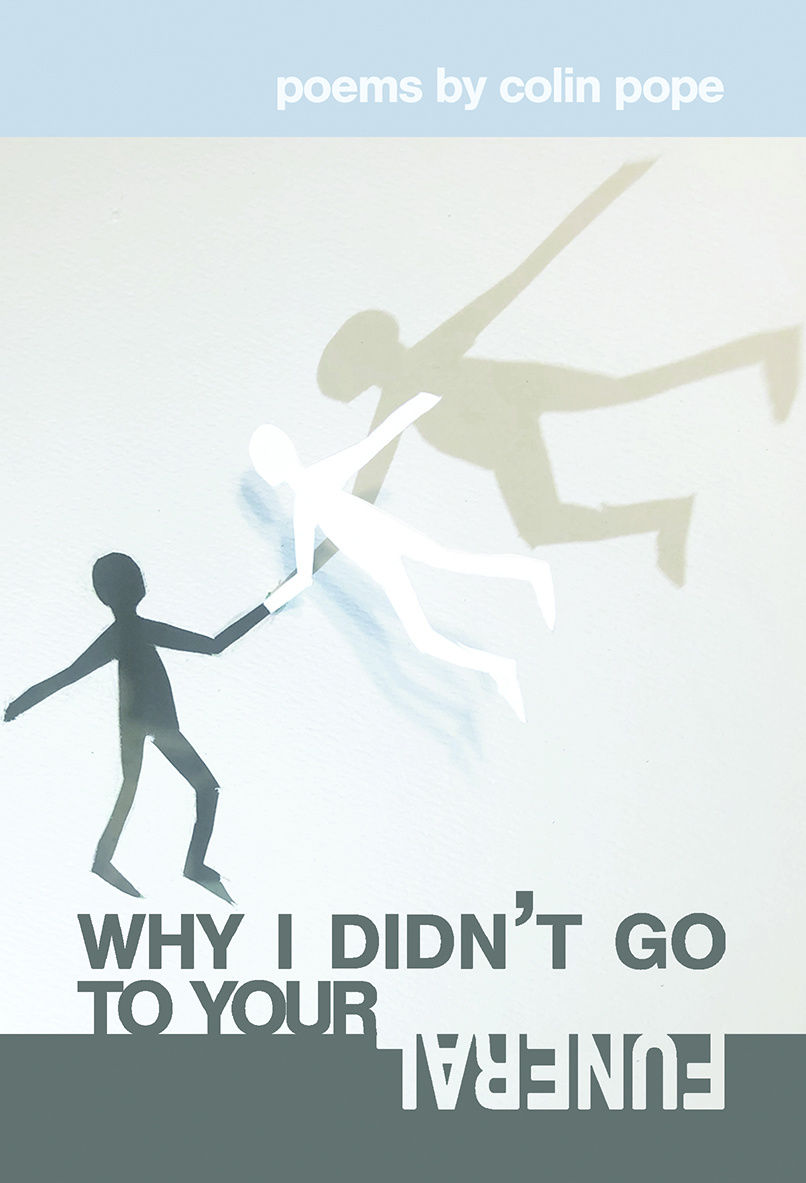

In his debut book entitled Why I Didn't Go To Your Funeral, Colin Pope explores themes of loss and recovery in 115 pages of poetry. Published by Tolsun Books earlier this year, the poems center around the suicide of a loved one, though often spin off into deeper contemplative moments surrounding the self's attempt to recover what is loss and also be recovered from the various faces of grief.

Perhaps the greatest accomplishment of the poems is within the spectacular failures of language throughout. Although the tone of the poems consistently remain as meditative and somewhat resigned, the language reveals a desperation to rediscover or re-body the deceased lover as well as cope with survivor's guilt. The poems often contain long lines, meaty stanzas, and multiple pages in length. There is little to no white space available, as if the poet only has this page to get it right; no expense is spared. And yet, the attempts of almost overwriting the page, moments of abundant, incredibly lush, and attempted high-brow philosophical moments in the language are slashed by the mundane:

"Advice: to keep from lunging and caterwauling

while they're lowering your lover's coffin

into the ground, momentarily imagine

Earth's revolution, which grinds at the precise speed

to stand, to cry so tears fall instead of fly."(42)

Followed by:

"Go on. Tell me what else there is to see."(44)

These undercuts of language both exemplify the rather hilarious inadequacies of language in times that we need it to perform the most as well as serves as an almost self-harm to the poet himself. When the language begins to reach too high, it is the poet who self monitors, who crashes the language, perhaps as a sort of conscious effort to stay in the real and not attempt to mask the bleak reality of death in the performances of language.

This monitoring of language brings us to an interesting line of questioning: who can speak for the dead? The poet seems to be wrestling with a similar struggle of wanting to recover the dead without taking the voice of said person. How do we write to recover, to revive, to re-body without taking too much for ourselves? How does a poet use the artifact of the book to preserve memory without manipulating that memory for their own comfort? For Pope, this balance seems to play out in how the poet portrays grief. What, at times, might seem like a book that keeps its subject at a distance, the deceased girlfriend never brought into full view, the evolution of grief serves as the truth that anchors the book, swerving away from the dangers of writing for another and instead providing an unflinching look at grief's interpretation of events and lasting effects on the self's grapple with loss and survival.

Grief is betrayed by the poet. Pope often removes the romance and sincerity in return for a more complete look into the cycles of grief; At times, the speaker's grief is self-serving and cold towards its subject, while other times, it is as readers would likely demand: longing, desperate, and burdened:

"Once in awhile, someone will ask

how you died. I have no problem telling them,

even enjoy it a little." (32)

And then in the poem on the following page:

"This must be depression, I'd sing, nodding, turning for the pet store

where they kept cats in furnished, glass apartments.

But there's that one stage where you start sweating at midnight

and don't stop until after sunrise, clutching the battery

from the overloud wall clock like a vial of antidote.

I'd been in it for a month or two." (34)

There is no great veil that this book attempts in the language that might disguise the horrendous nature of grief and how it shapes our understanding of events, our relationships with those missing, and our own emotional landscape. Grief, for this book, is the only character that can be recovered. The girlfriend, forever a ghost wading through the pages, the speaker, too, a ghost of himself. However, grief remains vibrant, unstable, moving. Even when difficult to look at, grief is the breath within the poems, the summer pavement that pains the bare soles while pushing the reader to go forward.

Why I Didn't Go To Your Funeral, presents a kind of stinging hurt that cannot be performed. It lives in the bed for which the language is written on, in the white space of the page that the poet has filled with a dummy language. No matter how far in you go, the forest of grief has no light to emerge into. The book wants to keep you in it, keep you as a part of the recovery attempt; as a witness. To read these poems is to willingly wound oneself, and there is small pleasures gained from feeling that you are a limb in the attempt to re-body:

"You'd have to lean in very close to hear

how many voices they're using,

to see the stitches a bolts

and how lovingly they've been put together." (33)

Colin Pope grew up in the Adirondacks. His poetry has appeared in Rattle, Denver Quarterly, Willow Springs, Slate, Ninth Letter, Los Angeles Review, and Best New Poets, among others, and his manuscript Prayer Book for an American God was a finalist for the 2018 Louise Bogan Award and the 2018 St. Lawrence Award. Colin is the recipient of residences and scholarships from organizations such as the Vermont Studio Center, the New York State Writer's Institute, and Gemini Ink, and he has won two prizes from the Academy of American Poets. He holds his MFA from Texas State University and is currently a PhD candidate at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater, Oklahoma, where he serves on the editorial staffs of Cimarron Review and Nimrod International.

Comments